José António Pereira, a Portuguese Merchant and Enslaver

By Raquel Machaqueiro | November 29, 2023

The São José Paquete d’África was just one of the many ships owned by José António Pereira (JAP), a very wealthy merchant from the city of Lisbon who, like many other merchants, was involved in slave trading. He started his career in the 1770s as a ship captain, which provided him with enough capital and experience to quickly become a ship owner, in a career path that was not unusual at that time.

Indeed, in the late 1780s he was already a known merchant, with business dealings in several Asian and European ports, and the African and American continents. JAP owned more than a dozen ships with routes connecting Lisbon, other cities in the north of Europe, the Malabar and the Western Indian Coast, Mozambique, Cacheu, Bissau, Benguela, Luanda, São Tomé, Brazil, Montevideo and Buenos Aires. He also had associates and business partners in all corners of the world, from Lisbon (Hermano Cremer VanZeller; Jacinto Fernandes Bandeira), to Rio de la Plata (José Viera Correa; Joaquim Vieira Andrade), to Brazil (Maranhão – António Bernardo Garrett), to Luanda (Anselmo da Fonseca Coutinho), to the North of Europe (Netherlands – Daniel Gildemeester), all of them directly connected to, and invested in slave trading. The vast network of JAP’s business associates as well as the territorial scope of his dealings attest to the complexity of the transatlantic slave trade (which went way beyond the Atlantic Ocean).

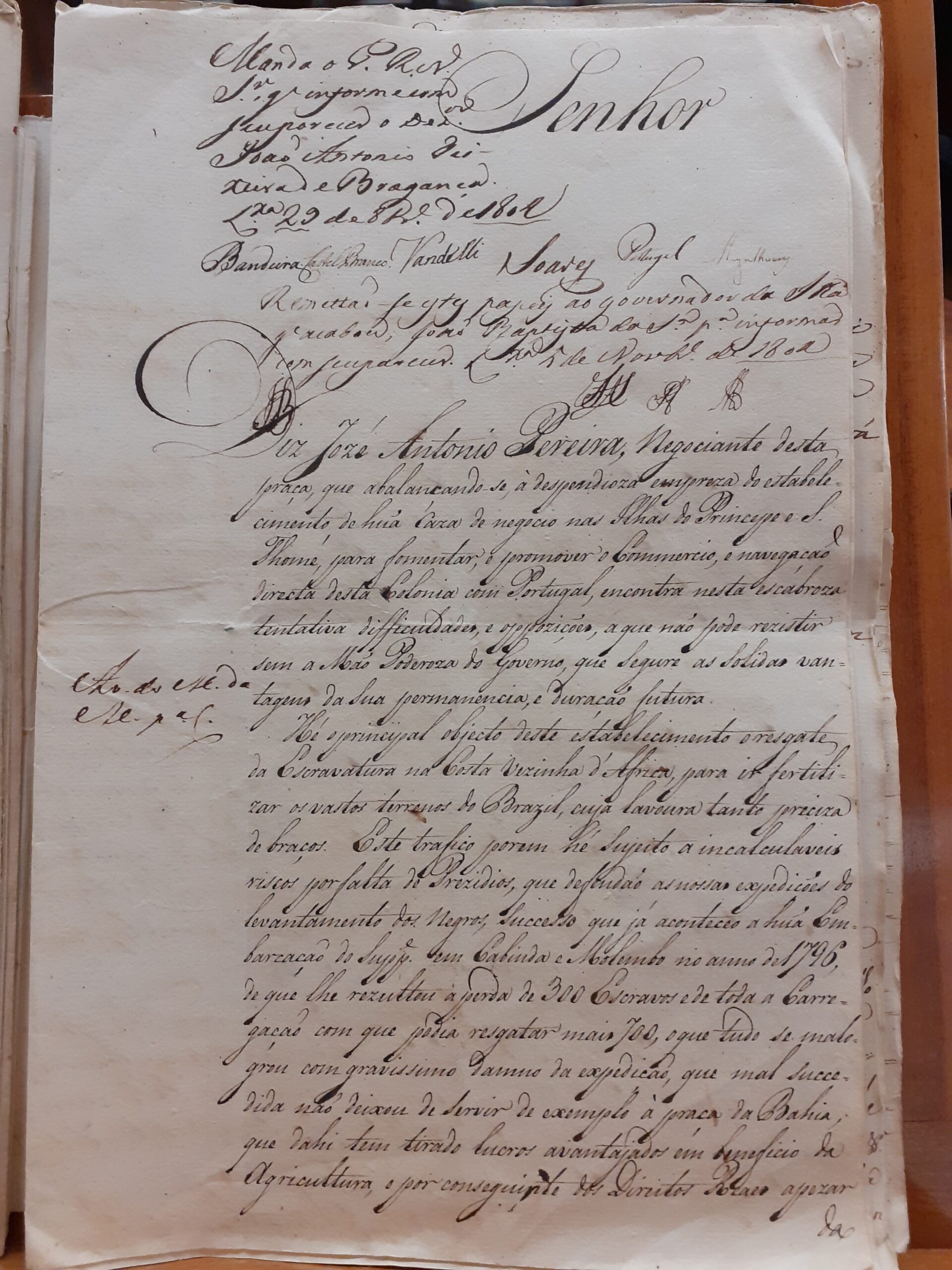

Pereira didn’t just use the regular circuits of the slave trade. In many instances, he actively sought to expand the trade, for instance, either by requesting the Crown for exemptions from the tight rules regulating the trade in the Asian ports, or by lobbying it to create the necessary conditions to capture and enslave Africans in São Tomé. In one document we found in the Portuguese archives, JAP pledges with the Portuguese authorities over the need to create in those islands fortified prisons to maintain the enslaved until their shipment to Brazil and prevent their rebellion – a circumstance that had already “cost” him 300 enslaved people who escaped their otherwise ominous fate.

Document where Pereira asks Portuguese authorities for support to maintain the risky slave trade business is in the Islands of S. Tomé e Príncipe (ANTT Maço 62, Cx. 202)

Pereira was also part of the first wave of Crown-authorized slave traders bringing enslaved people from East Africa to Brazil, which was prohibited up to 1792. The São José was perhaps the first legally sanctioned effort to bring slaves from Mozambique to Brazil.

These efforts to constantly expand the slave trade were only possible given JAP’s close relationships with the Portuguese Crown – something that we were able to confirm through research in the archives. Like other wealthy Lisbon traders, Pereira benefited from several tax exemptions (in the transportation of slaves to Pará, for instance), corresponded in friendly terms with many governors, and on many occasions successfully lobbied authorities in the defense of his commercial interests. The Portuguese Crown was highly indebted to merchants like Pereira since they were the main loaners to the Crown in times of need. These loans were then paid by granting them with exclusive access to monopoly contracts (of tobacco, soap, or salt), and with nobility statuses.

In 1794, Pereira requested the Crown to be granted the Knighthood of the Order of Christ, the most distinctive title of status in the Portuguese Empire, based on his work as a slave trader, “promoting the trade and the colonization of the Portuguese domains.” In this request, that was approved one year later, he was sponsored by other traders and by the Moçâmedes Baron, former governor of Angola.

The records also show that Pereira was extremely wealthy – and despite his dealings in many different goods, his main trade and basis for his fortune was the commoditization of human lives. Besides owning more than a dozen vessels, the several losses he suffered in his dealings – such as the São José and 212 of the enslaved onboard, the 300 enslaved who escaped during an insurrection (1796), or the loss of the ship Esperança, also taken following a slave insurrection (1796) – did not prevent him from continuing his business nor did they challenge his status. His profits could evidently sustain all these losses.

In 1799, he started the construction of a building-complex including a palace, several storage buildings, and a private dock for his ships on the shores of the Tagus River, in Lisbon. This large estate is currently owned by the Lisbon municipality, but with the exception of the palace, all the other buildings are vacant and abandoned.

Plaques identifying JAP’s estate with dates for the beginning and end of construction. Photo by Raquel Machaqueiro

Plaques identifying JAP’s estate with dates for the beginning and end of construction. Photo by Raquel Machaqueiro

After more than three decades of trading in human beings, JAP died in 1817 and was buried inside the Marianos Convent. Sixty-seven years after his death and fifteen years after the complete abolition of slavery in the Portuguese colonial empire (in 1884), the Lisbon municipality decided to officially name the street connecting his estate after him. To this date, the plate with his name stands at both ends of the street without any reference to who José António Pereira was, or how he built the fortune that allowed him to build the edifications that stand along the narrow street.

Narrow street named after Pereira. Photo by Raquel Machaqueiro

Narrow street named after Pereira, and plaque identifying it. Photo by Raquel Machaqueiro

This lack of information as well as the almost complete absence of JAP’s story from the official historical records speaks to the deliberate amnesia of the Portuguese public discourse regarding the role of the country in the transatlantic slave trade. Through the story of slave traders such as Pereira, the SWP is recovering a more complete history – one that does not shy away from reckoning with the Portuguese past and its role in the transatlantic slave trade.

Acknowledgements: The SWP thanks the Portuguese group Chapas for their collaboration in the archival research about José António Pereira and other Portuguese slave traders.